“Keep up a correspondence with household,” learn a letter written by Lacretia Johnson Flash’s late mom. “Chances are you’ll wish to return to Tennessee?”

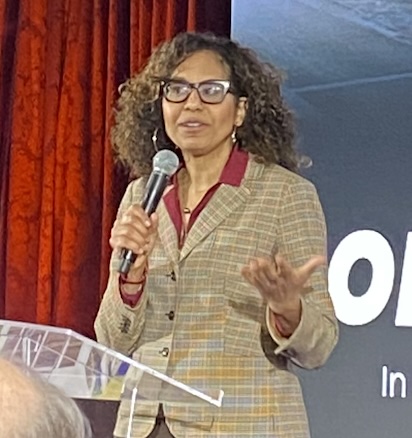

Practically 22 years later, Flash, senior vp for DEI, group, campus tradition, and local weather at Berklee School of Music, found an intriguing story about her ancestry. She hails from an formidable line of ancestors who had risen from slavery in center Tennessee to turn into a few of the first Black landowners in Perry County. However lo and behold, U.S. Congressman Brett Guthrie of Kentucky is a direct descendant of the individuals who enslaved Flash’s ancestors.

Guthrie has been representing Kentucky’s 2nd congressional district since 2009 and is now a senior Home Vitality and Commerce Committee member.

Reuters examined connections between two of Guthrie’s ancestors to uncover the reality as a part of a much bigger initiative to hint the lineages of greater than 600 of the nation’s main officeholders. Reporters discovered that Flash’s great-great-grandfather was enslaved by one of many congressman’s ancestors and the opposite her great-great-grandmother.

Throughout a visit to Tennessee, Flash visited with Helen Craig Smith, her mom’s cousin. Smith is the creator of Numbers: An Abridged Enumeration of the Peoples of Colour of Perry County, Tennessee, 1865-2000, which detailed the historical past of practically each Black resident within the county.

Flash’s ancestors, husband and spouse Tapp Craig and Amy Guthrie, have been the names that emerged out of a whole lot of pages of historic information. That they had assumed the surnames of their enslavers, farmers Andrew Craig and Andrew H. Guthrie. These males have been thought-about among the many wealthiest 2% of males in America, in response to the 1860 census.

“There is usually a sense of disgrace at privilege,” Flash instructed NBC Information. However she doesn’t blame at the moment’s Guthries for his or her ancestors’ selections.

“I don’t have a want for anybody to really feel responsible for actions of others previously,” she added. “Conversations about race may depart a scar, however they can even assist us heal.”

By 1871, after devoting years to tenant farming, Tapp and Amy had sufficient earnings for a down cost for about 90 acres alongside a tributary of the Tennessee River often known as Lick Creek. A white neighbor beforehand owned the land greatest suited to harvesting timber.

Shopping for land was one other alternative for Tapp, Amy, and different Black households to assist shut the academic hole. In line with Perry County Historic Society information fewer than half the county’s Black kids went to highschool as of 1885. For whites, the quantity was 90%. In response, Tapp constructed a college that doubled as a church. The land was used not solely to assist Tapp and Amy advance but in addition to assist others.

RELATED CONTENT: For America’s Political Elite, Household Hyperlinks to Slavery Abound