Across the flip of the twentieth century, Imperial Russia was a risky place. Residing situations had been harsh for most individuals, labour was exploitative and taxes had been excessive. There have been strikes and rebellions, and Jewish immigrants had been restricted to an annexed area often known as the Pale of the Settlement, the place “pogroms” – antisemitic riots and mob persecutions – had lengthy menaced.

Between 1903 and 1906, because the deadliest waves swept throughout 64 cities within the Settlement, a lady little one named Rivka hid in an alcove together with her household amid gunshots and damaged home windows; in 1907 her destiny was determined. She was to go away for America, together with her mother and father to comply with (they by no means did make it).

Aged 14, Rivka turned Rebecca, en path to New York by steamship. Magdalena Ball’s verse novel, Bobish (Yiddish for “grandmother”) charts her great-grandmother Rivka’s passage – and her life past.

Bobish is printed by Puncher & Wattman, an indie publishing home doing greater than its share to maintain alive novellas, verse novels and different kinds not thought of commercially viable in Australia. The quilt picture reveals a younger lady with the thousand-yard stare of the trauma survivor.

ALSO READ: Smoking: 4 compelling causes to give up for good

Complicated trauma

For a lot of with advanced trauma histories, leaving dwelling younger is much less a alternative than a necessity or compulsion. When the ache of a scenario – social or familial – outweighs the necessity for household bonding and the safety of group, you Get Out.

I used to be 15, a yr older than Rivka, after I fled: not from persecution, however from the powerlessness of a childhood in a household fractured by divorce and the stream of abusive males ushered into my mom’s life.

Complicated relational trauma is broadly outlined as cumulative and a number of traumatic occasions that includes interpersonal risk.

For some, this legacy quantities to an unrecognised, unaccommodated incapacity. Many work additional time to maintain a raging power struggle or flight response dampened right down to a level of practical equilibrium, in societal situations that regularly set off it.

Early starters like Rivka (or, Rebecca) are confronted with the dilemmas and dramas of the grownup world earlier than the neocortex has developed sufficient to grasp them, and with a traumatised amygdala and hippocampus firing on all cylinders.

Ball writes superbly of Rebecca’s departure, voyage and beginnings within the Bronx, evoking this difficult soup of expertise with a nod to childlike surprise, in poems like Ocean Mandela:

Her eyes turned a kaleidoscope spiralling with the water refracted

by tears she saved from falling …

The poem ends with an outline of the haunting previous she leaves behind:

reminiscence was Prussian Blue a cyanotype carried like ghostly love.

Bobish is transgenerational literary trauma testimony, which, as I argued in my monograph, The Poetics of Transgenerational Trauma, quantities to a type of intuitive-affective translation that “comes with its personal linguistic and artistic studying of the expertise of others”.

ALSO READ: Breaking the silence: The advantages of exposing psychological well being at work

Reclaim and Twenty first-century tendencies

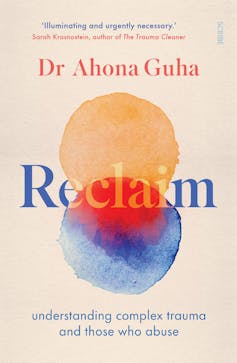

Studying Ball’s verse, woven with strands of nonfiction, household lore, and affective creativeness, alongside Reclaim: Understanding advanced trauma and those that abuse by Dr Ahona Guha, it’s as if Ball and Guha’s tasks had been born to intertwine.

Guha, a scientific psychologist and forensic professional, has penned a ebook about trauma that’s not literary, tutorial, or self-help: it’s a clear-eyed evaluation by a professionally certified, socially engaged and intimately knowledgeable writer. Guha purportedly wrote the ebook to redress fallacies in “a world that’s beset by trauma.”

This factors to a perplexing paradox. As Guha underscores, trauma is trending – at the very least on the socials. We’ve come a good distance since Charles Myers used the time period “shell shock” to explain the shattered males coming back from the trenches in 1915, and Freud outlined trauma as “any excitations from the skin that are highly effective sufficient to interrupt by the protecting protect”, thus flooding and binding the psyche (neuroscience has since confirmed traumatic damage as a re-wiring of the mind). As Guha says, this difficult course of “won’t ever be adequately captured by a TikTok video or an Instagram reel”.

Whereas elevated consciousness of trauma is welcome, it comes with a draw back. Guha observes that Western society’s tendency to medicalise and pathologise expertise results in troublesome emotions and conditions being outlined as traumatic when they might effectively not be.

She states, “the attain of know-how and social media has facilitated entry to simple and overly simplistic details about advanced psychological well being phenomena”, incessantly circulated by “individuals who have restricted or no formal {qualifications} in well being or psychological well being”.

This may increasingly sound like a shot at grassroots information, nevertheless it’s fairer to name it a level-headed acknowledgement that diagnostic phrases (resembling narcissist and psychopath) are being overused as buzzwords. And that some who stand to revenue use psychological well being and trauma terminology for unscrupulous functions, such because the peddling of non-public development thirst traps.

Guha discloses her personal historical past of advanced trauma to problem the disgrace and disparaging associations that keep on with trauma. I’ve been open about my historical past of advanced trauma for a lot the identical purpose.

ALSO READ: TNT Africa’s ‘Paper Spiders’ spotlights psychological well being consciousness

Signs celebrated and stigmatised

Whereas some signs of advanced trauma, resembling workaholism and fawning (in any other case often known as individuals pleasing) are culturally embraced and rewarded, others, resembling dependancy to unlawful substances, are denounced and criminalised.

Many within the jail system undergo from advanced trauma, as Guha highlights.

In a current examine, researchers on the UNSW Centre for Social Analysis in Well being confirmed systemic discrimination towards prisoners with histories of injecting drug use (as much as 58% of the jail inhabitants) upon launch from jail. (I used to be commissioned to write down a inventive work primarily based on interview transcripts and carried out by a group member to assist talk these findings to stakeholders and the general public).

It’s value noting that in response to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders in New South Wales are incarcerated at nearly ten occasions the speed of non-Indigenous Australians.

Some individuals in excessive locations hope their previous dependancy by no means involves gentle: public servants, medical professionals, and others whose careers could be at stake if outed. This bigotry is a hypocritical outrage. Assuming a sure baseline of restoration, why ought to individuals with histories of injecting drug use be considered as something however a useful office useful resource with a wealth of lived expertise?

There are additionally high-functioning drug customers and heavy drinkers who carry out effectively at work, although acceptability is determined by the context. For instance, you wouldn’t need to be operated on by a hungover surgeon, or journey on a bus with a stoned driver.

Regardless of Guha’s affordable reservations about persistent shortfalls in nuanced understanding of trauma, our society’s heightened give attention to trauma does maintain promise. The setting Rivka escaped, beset by antisemitic assaults and pre-revolution tensions, and the world she entered when she docked – colonised Lenape land teeming with displaced individuals; illness ran rife within the ghettos and the murder fee was excessive – had been hotbeds of trauma transmission. These populations had been nearly solely uneducated about trauma’s pernicious potential – and largely unaided.

Folks with early advanced trauma histories are among the many most spectacular innovators and successes throughout a variety of industries, propelled into prominence or energy by a fierce inside drive.

However many childhood and adolescent advanced trauma survivors are sluggish achievers. We develop into our abilities and skills – assuming we survive lengthy sufficient – after navigating impediment programs of linked situations, together with melancholy, anxiousness problems and different power sicknesses.

We rise in our fields after spending years studying the essential life expertise and coping methods much less traumatised individuals take as a right. Some are thought of low achievers, spending a lifetime maintaining their heads above water in oceans of emotional ache that will drown lots of those that deem them inferior.

ALSO READ: TNT Africa’s ‘Paper Spiders’ spotlights psychological well being consciousness

A reclamation

Bobish commemorates a life that was each exceptional and unremarkable. It proclaims the value of those that might seem on the floor to be low achievers, however whose continued existence within the face of adversity is itself an affirmation of spirit over trauma.

Ball’s rendering of Rebecca’s trials isn’t melodramatic, even when “Beckie” is denied dignity by indifference or hostility. For instance, in Information to the USA for the Jewish Immigrant, Ball is even-toned:

A doctor and a nurse

are in attendance.

(Sickness is forbidden

if you happen to’re marked as sick

you’ll be despatched again.)

The verse novel, as a type, is at all times an attention-grabbing alternative – and it’s the excellent car for memorialising Rebecca. Whereas it’s not identified for bestseller gross sales, it makes a significant contribution. Notable outings embrace Dorothy Porter’s famend Monkey’s Masks and Seahorse by San-Francisco-based Australian poet, Natasha Dennerstein, about transitioning through the Eighties, which reads like a verse novella. (Dennerstein’s About A Woman is overtly marketed as a “novella in verse”.)

The great thing about the verse novel (or verse novella) is that it could inform a narrative with out being constrained by prose’s calls for for filled-in gaps and transitions between occasions. Good verse leaps over temporal gaps; the reader is launched from the expectation of a blow-by-blow account, free to enter and inhabit the communicative area between poems as a part of the narrative rhythm.

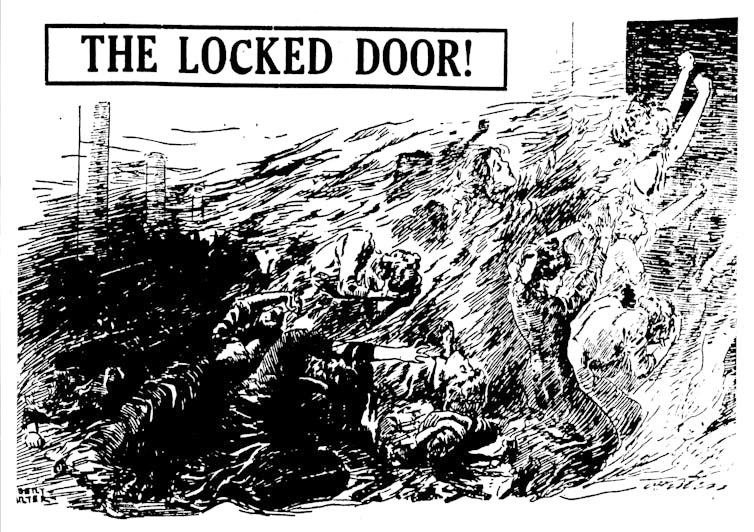

Rebecca’s New York trajectory unfolds like a case examine of the traumatic operations Guha maps in Reclaim. She will get a job on the notorious anti-unionist Triangle Shirtwaist Manufacturing unit, the place bosses lock within the garment employees, to maximise productiveness and stop theft. (Miraculously, Rebecca just isn’t at work the day of the hearth that kills 146 individuals.)

She meets a captivating fish smoker who speaks 11 languages. A fellow Jewish immigrant and one-time scholar finding out to turn into a Rabbi, he’s relegated to working a pushcart downtown close to the tenements. They quickly wed.

Guha introduces shorthand to higher perceive trauma. “Massive T” stands for life-threatening trauma; “little t” is for subtler types of trauma that “typically go unrecognised by victims or individuals round them”. The tangled spectre of each infuses Rebecca’s marriage.

Guha foregrounds “relational trauma” – trauma that happens in a relational context – noting that childhood relational trauma sometimes shapes “somebody’s complete identification and the best way they assume and really feel”. This oozes from the web page in Ball’s depictions of Rebecca.

Guha unpacks “trauma responses” (resembling fight-flight-freeze-tend-befriend defences) as the first mechanisms for managing traumatic rigidity. The fish smoker is caught in struggle mode and seems to be a violent, alcoholic presence within the dwelling.

Ball holds him accountable, however handles him with compassion. In Pickled Herring Pushcart, Ball imagines strolling “backwards into the tableau” to take a seat with him “in some crack between our worlds the place we might converse freely”. She imagines him taking her fingers to:

Whisper all the things

so I’d perceive

contrition and trauma

in equal measure.

And in La Grippe, she tells her ailing great-grandfather, nursed by Rebecca:

Ach, fish smoker. You can not change the previous.

It wends its manner by the funhouse of time in antigenic drift and shift,

viral particles, infecting the long run.

Damage individuals harm individuals

Right here, the 2 texts intersect poignantly. Probably the most admirable factor about Guha’s admirable ebook is its advocacy for these caught within the darkest realms of trauma’s slipstream: the least likeable amongst us, who act out in essentially the most socially unacceptable methods. Guha calls for we search to grasp not solely traumatised sweethearts (those that invite sympathy) but in addition individuals who exhibit alienating, infuriating or scary trauma-fuelled traits.

Trauma denied and/or unconscious offers life to the adage “harm individuals harm individuals”. Disengaged from the weak roots of their struggling and in a state of unrelenting response, traumatised individuals can turn into traumatisers. Guha clarifies, although, that “dangerous behaviour arises from a confluence of things” and trauma alone doesn’t clarify abuse.

The fish smoker was not a monster. My mom’s companions weren’t monsters. They had been broken and socially conditioned males who broken different individuals. A historical past of advanced trauma doesn’t excuse violations, nevertheless it is incessantly on the core of them – and we ignore that at our peril. “We’ve got neat binaries in our minds: victims and perpetrators,” states Guha. In some instances, that neatness belies a chaotic crossover.

It appears like feminist sacrilege to say this, such is the attachment to the binary. Guha’s willingness to confront this murky terrain is brave, and the dangerous nature of the transfer is likely to be why Guha options a number of ladies within the chapters targeted on dangerous behaviour.

Trauma as a political instrument

Guha’s attraction is essential, as a result of the failure to know the trauma behind many crimes offers rise to dehumanisation and but extra trauma – generally within the type of state violence, resembling Aboriginal deaths in custody and the Northern Territory Emergency Response, in any other case often known as “The Intervention”.

Guha’s chapter on “The Politics of Trauma” is a crucial contribution. Guha is uncommon amongst psychology-trained authors in taking a agency political stance round “lowering reliance on policing and incarceration-based responses” and advocating for an “equitable trauma-informed society”.

“We fail trauma victims when we don’t establish them, and when we don’t present acceptable care”, she says. (For instance, the federally funded psychological well being plan is insufficient for advanced trauma, and the 20 subsidised periods per yr permitted throughout COVID lockdowns had been scaled again to 10 in 2022.)

However there are worse issues than being ignored. Too typically, leaders actively allow structural drawback and are chargeable for gross failures of governance that themselves show traumatising, as was the case with the disreputable Robodebt Scheme. The true measure of its malice has come to gentle by way of the Royal Fee, which Rick Morton has lined exhaustively in The Saturday Paper and The Month-to-month.

The driving pressure of Bobish is Ball’s veneration for Rebecca, and whereas the delicate characterisation of her great-grandfather is commendable, she doesn’t shrink back from the ache he brought about Rebecca and the household. Finally, Ball has crafted these poems – in session with family and her aunt’s memoir and diaries – to honour her bobish.

Rebecca confronted continuous hardship and died comparatively younger partially as a result of trauma took its toll on her well being. However Ball additionally reveals her loving and laughing, reanimated in scenes of household merriment and tenderness.

Each Bobish and Reclaim push again towards widespread worth judgements that much less traumatised – and extra privileged – individuals make about these residing with advanced trauma.

One by wanting again; the opposite by wanting round soberly – and alluring us to construct a “trauma-informed group” and transfer towards a extra simply future.

Article by: Meera Atkinson. Affiliate Lecturer in Inventive Writing, College of Sydney

This text is republished from The Dialog beneath a Inventive Commons license. Learn the unique article.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE ARTICLES BY THE CONVERSATION