By Amy Maxmen

GREENVILLE, Miss. — Cedric Sturdevant wakened with “a little bit of despair” however made it to church, as he does each Sunday. In just a few days, he would drive from Mississippi to Washington, D.C., to hitch HIV advocates at an April rally towards the Trump administration’s actions.

It had clawed again greater than $11 billion in federal public well being grants to states and abruptly terminated hundreds of thousands of {dollars} in funds for HIV work in the US. Testing and outreach for HIV faltered within the South, a area that accounts for greater than half of all HIV diagnoses.

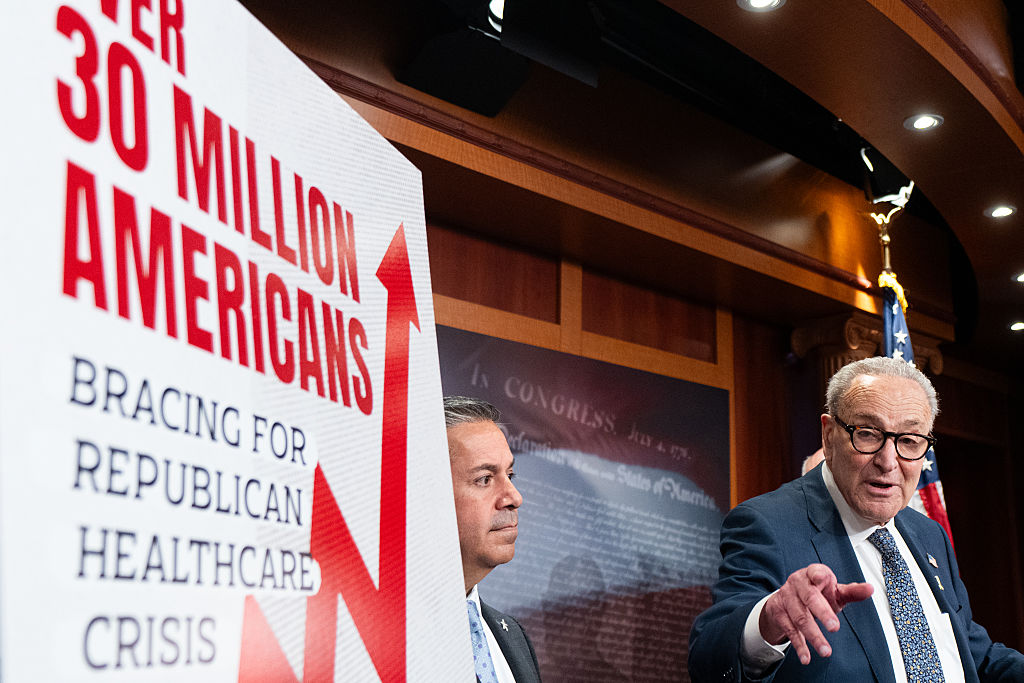

Harmful adjustments loomed: To compensate for tax cuts for the rich, Trump’s “large, lovely” invoice and finances proposal for fiscal yr 2026 threaten to curtail Medicaid, which supplies well being protection for folks with low incomes and disabilities. About 40% of adults with HIV depend on it for his or her lifesaving therapies.

Additional, the finances proposes to remove all HIV prevention packages on the Facilities for Illness Management and Prevention. This alone might result in an extra 14,600 HIV-related deaths inside the subsequent 5 years, based on one evaluation.

Trump’s finances proposal additionally would cancel a serious grant that gives housing help for folks with HIV. And it will finish a strategic initiative to increase HIV providers in minority communities, and one other to help the psychological well being of individuals of coloration with HIV or prone to an infection.

“President Trump is dedicated to eliminating radical gender and racial ideologies that poison the minds of Individuals,” a White Home addendum to the finances says. Letters terminating HIV grants used related language, concentrating on “range,” “fairness,” and “gender minorities,” phrases that focus sources the place they’re wanted most. Black and Latino folks account for about 70% of latest HIV infections within the U.S.

The cuts have an effect on Sturdevant personally. He’s a homosexual, Black man residing with HIV and the co-founder of a grassroots group that combats well being disparities within the Mississippi Delta, one of many poorest areas of the nation.

That morning at church, an in depth good friend, pastor Jerry Shelton of Anointed Oasis of Love Ministry, requested Sturdevant to assist him ship a sermon about resisting the urge to surrender when life is tough. “The storm could come, however I shall not be moved!” Shelton preached, directing the congregation to strategy adversity with confidence in themselves and in God. “Stroll boldly!” he shouted.

After the service, Sturdevant resolved to deliver the identical power to Washington. He’d inform his colleagues that they’re survivors, he stated. He’d inform them, “Let’s get collectively and make a plan.”

Prior to now few months, HIV advocates have begun to arrange and strategize methods to restrict the harm as federal funds are slashed and inflammatory rhetoric rises.

“It’s a very scary time to be Black, queer, and residing with HIV,” stated Marnina Miller, co-executive director of the Optimistic Girls’s Community, a nationwide group for girls residing with HIV. “However I’m grateful that I’m a part of a neighborhood that won’t bow down.”

“Individuals are not giving up,” stated June Gipson, the CEO of a well being care nonprofit, My Brother’s Keeper, in Mississippi. Then she referenced the Nineteen Eighties cartoon the place heroes mix forces to create a brilliant robotic to defend the universe:

“We’ve received to type Voltron.”

The Weight of Stigma

Sturdevant usually reminds his colleagues of all of the HIV motion has overcome. Within the Nineteen Eighties, the federal government refused to acknowledge HIV as homosexual males died younger. As soon as highly effective therapies had been obtainable within the Nineteen Nineties and early 2000s, the general public well being institution largely uncared for Black folks with HIV, particularly within the South. In that interval, the demographics of the epidemic shifted away from white, upper- and middle-class homosexual populations in liberal states. Half of latest diagnoses right this moment are within the South and a 3rd are amongst folks with low incomes.

When Sturdevant first examined constructive for HIV in 2005, he didn’t search remedy. He saved his analysis hidden from family and friends as a result of he knew how folks talked about HIV. They thought of it a loss of life sentence, a punishment for irresponsible conduct, or a illness that might infect them by a contact or a shared bathroom seat — which it can’t.

“I believed my household was going to disown me,” he stated.

A yr later, his weight plummeted as a result of he couldn’t maintain down meals or water. Gaunt and feverish, he went to the hospital and realized he had AIDS. His mom slept at his hospital bedside for 2 weeks: “She stated, ‘God received you.’”

As soon as he regained his well being, Sturdevant resolved to take care of others in his place. Scientists had developed highly effective HIV medicine that, if taken each day, remodel it from a loss of life sentence right into a manageable persistent illness during which an individual’s virus ranges are so suppressed that they can not unfold HIV to others. And policymakers ensured that nearly everybody within the U.S. with HIV might get handled no matter their capacity to pay, largely due to Medicaid and the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program.

However HIV consultants had failed to beat a key drawback: Roughly a 3rd of individuals residing with HIV within the U.S. don’t get handled or don’t take the medicine usually sufficient to be virally suppressed. Viral suppression charges are higher in lots of African nations than in America.

To hunt remedy and keep it up, Sturdevant understood, folks needed to have primary wants like meals and housing met and, as importantly, a way of belonging and empowerment. At his first job at an HIV group in Jackson, Mississippi, Sturdevant usually checked in with purchasers who didn’t have members of the family to help them. He hosted gatherings at his house and even provided it up as a spot to remain. He has taken on the function of pop or uncle to many. “We referred to as ourselves the household of affection,” he stated.

He noticed how care bolstered lives, however the federal authorities wanted knowledge to drive its strategy to HIV.

In 2012, the CDC expanded its in-depth surveys to study extra concerning the lives of individuals prone to HIV and of these with HIV who weren’t virally suppressed. The surveys revealed what Sturdevant knew: A disproportionate variety of them grappled with unstable housing, meals insecurity, despair, and nervousness. Many contributors agreed to prompts like, “Having HIV makes me really feel that I’m a nasty individual,” or “Most individuals suppose that an individual with HIV is disgusting,” or “Most individuals with HIV are rejected.”

The info confirmed policymakers that to curb the epidemic, they wanted to deal with underlying issues that individuals with HIV confronted. Federal funds started to movement to grassroots teams embedded in marginalized communities.

Public well being researchers folded Black church buildings into the hassle, recognizing them as hubs of volunteerism and as leaders of social actions. Though church buildings within the U.S. had traditionally fueled stigma towards sexually transmitted ailments, Amy Nunn, a public well being researcher at Brown College, stated each pastor she talked with was keen to assist. It paid off. In Kansas Metropolis, for instance, researchers discovered that congregants who went to Black church buildings concerned in HIV schooling and outreach had been greater than twice as more likely to be examined.

Group-based interventions labored: New HIV infections dropped by 12% from 2018 to 2022.

Now the grassroots teams which have been so efficient are in jeopardy and the in-depth surveys have halted because the Trump administration cuts funds and lays off CDC workers. Some well being departments have issued stop-work orders to community-based teams that check folks for HIV and join them to remedy as a result of federal HIV grants are unusually delayed. And because the Division of Well being and Human Companies continues to cancel HIV grants, the administrators of grassroots teams anticipate extra cuts.

“Loads of them are new and don’t have the sources to outlive a yr with out funding,” stated Masen Davis, govt director of Funders Involved About AIDS.

One such group is Sturdevant’s.

‘Belief the Course of’?

In 2017, Sturdevant returned dwelling to the Mississippi Delta to launch a nonprofit, Group Well being PIER, in one of many poorest and most medically underserved components of the nation. The common life expectancy within the Delta is 68, a decade shorter than the nationwide common. The disenfranchisement of its majority-Black inhabitants stems from the area’s historical past, during which insurance policies concentrated wealth and energy among the many minority-white inhabitants throughout the period of cotton sharecropping, Jim Crow legal guidelines and segregation, and, lately, on account of gerrymandering.

Sturdevant arrange store in Greenville, close to a Black church that served as a headquarters for civil rights activists within the Nineteen Sixties. In a small workplace, his workforce organizes well being occasions, exams folks for HIV, and connects those that check constructive with remedy and housing help, funded by federal packages like Ryan White.

“Whites have been getting Ryan White and different packages for years and residing wholesome,” stated Ashley Richardson, administrative assistant of Sturdevant’s group. “Round right here, Black individuals are simply now attending to the purpose the place we all know there are sources to assist.”

Currently the workforce fields calls from folks with HIV who’re terrified they are going to lose their lifesaving medicine and housing if authorities packages now not assist with the fee.

Sturdevant worries about preserving his workers employed and his neighborhood secure. On the drive dwelling from the April occasion in Washington, he drearily recounted conversations with Republicans in Congress: “They mainly all stated belief the method.”

The heads of nationwide HIV organizations have stepped up their advocacy, asking Congress to oppose cuts in President Donald Trump’s finances request, stated Gregorio Millett, director of public coverage on the Basis for AIDS Analysis, a nonprofit often known as amfAR.

Emily Hilliard, spokesperson for the Division of Well being and Human Companies, responded to queries from KFF Well being Information by writing, “Important HIV/AIDS packages will proceed below the Administration for a Wholesome America.” But the administration’s proposed finances for HIV prevention represents a 78% discount in contrast with fiscal yr 2025, based on a KFF evaluation.

HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has fostered skepticism about scientific info regarding HIV, with out citing proof. “Any questioning of the orthodoxy that HIV is the only reason for AIDS stays an unforgivable-even dangerous-heresy amongst our reigning medical cartel,” he wrote in a 2021 ebook.

Not Bowing to Limitations

Researchers and HIV advocates are hashing out methods to fill within the vacuum in HIV care that the federal government is poised to go away. For many years, it has pushed priorities, coordinated a constellation of HIV teams, and tracked the epidemic. Leisha McKinley-Seaside, CEO of a coaching institute, Black Public Well being Academy, in Atlanta, stated folks should keep in mind that wasn’t all the time the case.

“This large trade we’ve got right this moment was created by dedicated people on the grassroots degree, who had been going to assist folks reside with HIV or die with dignity, by any means mandatory,” she stated.

One concept is to have bigger, established HIV organizations associate with nascent teams in underserved areas. The larger ones stand a greater probability of garnering vital personal donations. And by taking up the fiscal administration of grants, giant teams might allow small ones to dedicate time to service fairly than fundraising, McKinley-Seaside stated.

One other technique, stated Kathy Garner, govt director of Mississippi’s AIDS Companies Coalition, is to fill gaps by coordinating with church buildings and nonprofits devoted to meals help, housing, or psychological well being.

“One of many options goes to be civil society stepping up,” Garner stated. “That’s an outdated time period for folks caring for one another, outdoors of the federal government.”

“We’re going to want to ramp up our providers in all types of how, and well being and HIV shall be part of that,” stated Bishop Ronnie Crudup of New Horizon Church Worldwide in Jackson, and a member of Mississippi Religion in Motion, a coalition of African American church buildings concerned in HIV.

“I’ve actual issues with what the Trump administration is doing, and the way it will play out for the well being of individuals in a poor state,” he stated.

Nationwide teams, akin to AIDS United, have been talking with company funders and philanthropies about constructing a pooled fund to assist maintain HIV organizations throughout the U.S.

Philanthropy for HIV has by no means come near matching federal {dollars}, nonetheless. Non-governmental funders put $284 million towards HIV within the U.S. in 2023, in contrast with about $16 billion in annual federal funds for HIV lately.

“The reality is there isn’t a manner for philanthropy to make up for the cuts from the federal authorities,” Davis stated. “I believe we are going to see new infections rise inside 18 months, which is heartbreaking.”

Sturdevant focuses on survival, not forecasts. “This isn’t going to be simple,” he stated, “however we have to preserve combating for individuals who don’t have the struggle in them.”

KFF Well being Information is a nationwide newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about well being points and is without doubt one of the core working packages at KFF — an unbiased supply of well being coverage analysis, polling, and journalism. Study extra about KFF.