Yemeni Scottish filmmaker Sara Ishaq, who was Oscar-nominated in 2012 for her quick documentary “Karama Has No Partitions,” is in post-production on her fiction characteristic debut, “The Station,” which the director can be taking to the Venice Manufacturing Bridge’s Closing Minimize workshop, working from Aug. 31 – Sept. 2.

The movie facilities on a women-only gasoline station in a segregated, war-torn city and follows Layal, a younger lady confronted along with her 12-year-old brother’s rising need to interrupt free and change into a person. When Layal’s estranged sister unexpectedly reveals up with a proposition for him, the siblings’ relationship is put to the check.

That includes a solid of principally non-professional Yemeni actors, “The Station” is written by Ishaq and Nadia Eliewat and produced by Display Challenge and Georges Movie, in co-production with One Two Movies, Kepler Movie, Barents Movie, The Imaginarium Movies, Setara Movies and Ta Movies. Eliewat of Amman-based Display Challenge is the lead producer. Paradise Metropolis Gross sales is dealing with world gross sales rights.

“The Station” — which Ishaq describes as “an ode to the individuals of Yemen” — marks the most recent cinematic chapter within the director’s long-running relationship with the nation of her beginning. Ishaq was raised in Yemen however left on the age of 17 to reside along with her mom in Scotland. It was whereas she was there, working towards an MFA in filmmaking in Edinburgh, that the Arab Spring erupted in 2011. She instantly booked a flight to Yemen, arriving on the day that protests broke out within the capital, Sanaa.

Although she would discover work with overseas information businesses and documentary crews reporting on the revolution, Ishaq felt that their views had been inevitably “far faraway from what the truth was.” She had been making movies in Yemen since 2007 and was decided to seize a extra nuanced and complicated portrait of the nation. “There’s all the time this othering that finally ends up occurring [with foreign observers], even when it’s inadvertent,” she stated. “So for me, it was essential…to attempt to inform these tales from inside.”

That dedication led to Ishaq’s debut quick documentary “Karama Has No Partitions” (2012), in regards to the 2011 bloodbath of greater than 50 peaceable protesters by pro-government gunmen, which garnered nominations for a BAFTA and an Academy Award, and the feature-length documentary “The Mulberry Home,” a extra private household research set in opposition to the backdrop of the revolution, that premiered at IDFA in 2013.

“The Station” was impressed by real-life occasions that occurred when Ishaq returned to Yemen in 2015. There, she encountered a women-only fuel station within the coronary heart of her hometown, Sanaa. It was populated by girls from all walks of life and all corners of the nation who “got here along with one widespread objective — to maintain and help their households.”

“We’d by no means seen something like that earlier than,” stated Ishaq. “Girls all the time performed an enormous position in [Yemeni] society. However at this explicit time, the place males had been both laid off their jobs, or they had been drawn to the combating, girls actually got here to the forefront…. They had been nonetheless working the family but in addition making an attempt to determine methods to generate an earnings for his or her households.”

Whereas queuing for the scarce gasoline that was a “lifeline” for the war-torn populace, stated the director, “girls chatted from their automobile home windows, shared meals and drinks, ‘car-schooled’ their kids and exchanged tales.” Regardless of the occasional dispute, the temper was full of life and communal, with Ishaq describing it as “a utopia inside this dystopian world.”

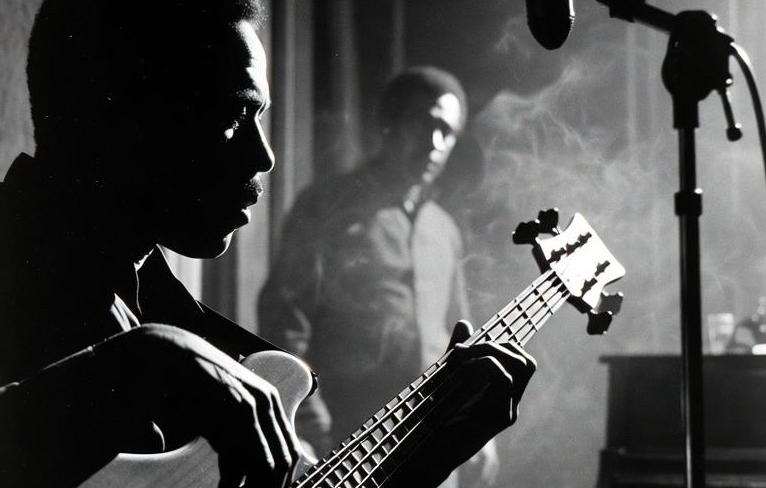

“The Mulberry Home” premiered at IDFA in 2013.

Courtesy of IDFA

The director had initially hoped to movie “The Station” as a documentary, however there have been too many sensible obstacles to beat. Combating between numerous factions typically made it too harmful to go away the home, whereas many Yemeni had been reluctant to seem in entrance of a digital camera, which incessantly aroused suspicion. Ishaq cited an expression that was typically utilized in Yemen throughout the revolution: “Carrying a digital camera is extra harmful than carrying a gun.”

She returned to Scotland with a trove of fabric that she was struggling to make sense of. In the meantime, the information studies from Yemen had been giving a really completely different picture of a rustic she knew in all its heartbreaking complexity. “The main target was all the time in regards to the poverty of Yemen, and the destruction, and the devastation,” she stated. “It was much less in regards to the individuals, their humanity, their power and resilience, inside the context of a ravishing nation that’s in actual fact not poor in any respect, however one which has been exploited and impoverished over the a long time.”

It might take roughly eight years for that imaginative and prescient to seek out its type in a feature-length script, requiring Ishaq to jettison a lot of what she’d discovered as an award-winning documentary filmmaker. As soon as she managed to beat the “inventive paralysis” that accompanied her “documentary mindset,” nevertheless, the director discovered it liberating to distill her experiences right into a fictional narrative whereas additionally “creating one thing that’s visually fully completely different from my documentary fashion.”

“The Station” is about in what Ishaq describes as a “speculative area,” a universe that capabilities as a “microcosm of Yemeni society” however is nonetheless “unbound by a particular time or place.” Drawing on the nation’s previous and current, it “displays the gradual unraveling of the social material” in a spot fractured by warfare, overseas invasions and inner political strife, however refracts that shared historical past “into an absurd, typically exaggerated parallel world.”

“At its coronary heart, the story will not be about politics. It’s about individuals, their relationships, contradictions and resilience — what makes us not solely Yemeni, however human,” stated Ishaq. “It’s an ode to the individuals of Yemen who’ve endured and survived years of warfare with dignity, humor and power.”