9 letters. Two phrases. And a historical past like no different.

Black hair is extra than simply strands of keratin. The afros, locs, braids, twists, and Bantu knots are a cultural archive, a political assertion, and a supply of tradition and pleasure. Black hair is time spent in neighborhood at barber outlets and hair salons, and with household in grandma’s kitchen as kin discuss whereas getting their braids taken down.

However for hundreds of years, Black hair has additionally been a goal — discriminated towards in lecture rooms, policed as unprofessional within the workplace, condemned within the navy and generally even within the mirror. The message to Black folks, and girls specifically, has all the time been clear.

Your hair is an issue.

The tales are in every single place: Texas highschool pupil Darryl George suspended for his locs Fort Price resident Kerion Washington denied a summer time job at Six Flags attributable to his dreadlocks. Louisiana lady Imani Jackson fired from her job for carrying her pure hair.

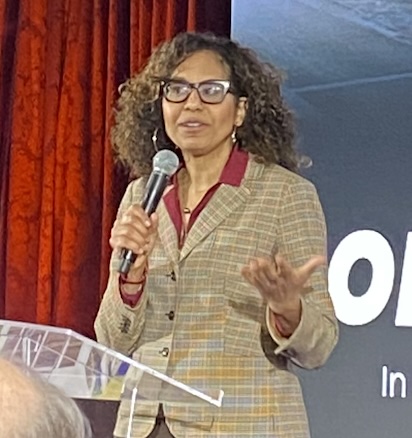

“Our hair is usually misunderstood and careworn, compelled to do issues that go towards its nature, like withstanding excessive warmth, harsh chemical substances, rubbing stocking caps and glue, poisonous laden artificial hair, and wigs to evolve with Eurocentric magnificence requirements and style developments,” says Dr. Afiya Mbilishaka, a scientific psychologist and hairstylist who researches the intersection of Black hair and psychological well being.

However attempting to evolve to Western magnificence requirements — mushy, straightened, maybe calmly kissed by the curling iron — could be hazardous to your well being.

Final month, an Environmental Working Group evaluation discovered that, out of some 4,000 hair and sweetness merchandise marketed to Black girls, 80% of them “include at the least one reasonably hazardous ingredient — and most include a number of.” That features hair-care merchandise with chemical substances that elevate the chance of most cancers.

That’s why Dr. Raven Baxter, a scientist and social media influencer generally known as Raven the Science Maven, formally declared a truce along with her hair — by reducing all of it off.

“I’ve totally divested from the lengthy hair industrial advanced,” she stated in a current Instagram submit. Black girls, she stated, are at struggle with their hair, “and it’s a struggle we didn’t even begin. And I’m not gonna battle in that struggle. It’s inflicting me pointless stress.”

The CROWN of Black Hair

In recent times, there have been indicators that society is taking the battle critically. In 2019, California grew to become the primary state to cross the CROWN — Making a Respectful and Open World for Pure Hair Act. Former California State Senator Holly J. Mitchell, a Democrat and a Black lady, authored the invoice partially after stories of Black girls being fired or disciplined within the office due to their coiffure.

As of April 2025, 27 states have handed the CROWN Act into regulation.

Tuskegee College pupil Haileigh Coach, 21, says the regulation shouldn’t be vital, however needed to occur “due to the discrimination we face. I believe Black hair is policed not simply at school however within the office.”

The info tells the story: In line with the CROWN 2023 Office Analysis Examine, about 20% of Black girls aged 25 to 34 reported being despatched house from work due to their hair. Black hair is 2.5 occasions extra more likely to be perceived as unprofessional, and greater than half of Black girls say they consider they should put on their hair straight for a profitable job interview.

Angel Mayfield, 20, a Florida A&M College pupil, says she is certainly one of them, though she has contemplated whether or not to put on a pure model. What stops her, she says, are the stereotypes typically related to pure Black hair.

“We all the time have to consider methods to make ourselves look acceptable or skilled,” she says. “I don’t suppose that’s proper.”

For many of her life, Mayfield says, her hair was chemically straightened; she will be able to’t bear in mind the primary time her dad and mom put a relaxer in her hair. When she received sufficiently old to make her personal decisions, Mayfield was the primary in her household to cease straightening her hair. It was extra than simply prioritizing her hair well being. It was, she says, about reclaiming her energy.

Centuries of Discrimination

Earlier than the newly enslaved have been shipped to America, the primary act of the enslaver typically was to chop off their hair — an act of dominance, management, and dehumanization.

“The shaved head was step one the Europeans took to erase the slave’s tradition and alter the connection between the African and his or her hair,” authors Ayana D. Byrd and Lori L. Tharps wrote within the ebook “Hair Story,” which paperwork the Black hair expertise in America. With out their distinctive tribal hairstyles, they wrote, “Mandingos, Fulanis, Ibos, and Ashantis entered the New World, simply because the Europeans meant, like nameless chattel.”

White enslavers ridiculed Black options, compelled Black girls to undertake white magnificence requirements, and created a social hierarchy, elevating these with lighter pores and skin and straighter hair. Pure Black hair — from tightly coiled, cottony, and coarse to loosely curled and finely textured — was condemned as soiled, tough, and unkempt.

“Effectively could we scoff at black skins and woolly heads, since each mannequin set earlier than us for admiration, has a pallid face and flaxen head,” author William J. Wilson wrote in 1853 in “Frederick Douglass’ Paper.” By the 1770s, the time period “good hair” emerged to change into an enduring a part of the Black magnificence lexicon: the nearer Black hair got here to white hair texture, the higher it was assumed to be.

That commonplace made millionaires of Madam C.J. Walker, a Richmond beautician. Within the Nineteen Twenties, Walker patented strategies of straightening out Black kinks and coils. Over time, chemical relaxers grew to become one other instrument to provide Black of us that modern Eurocentric look, an ordinary that dominated Black magnificence tradition for generations.

Throughout the Black Energy motion of the Sixties and ‘70s, Black Individuals embraced their textured hair by carrying an Afro as an indication of resistance and pleasure. Later within the Nineteen Nineties, field braids grew to become well-liked; within the early 2000s, with the rise of blogs and YouTube, the pure hair motion took off.

Going Pure

Coach, the Tuskegee College pupil, says she has a love-hate relationship along with her hair. Rising up, she received her hair pressed for particular events and holidays, a ritual she didn’t get pleasure from.

“The new comb was on the range, the grease was out, and the towel was there. It was dreadful,” she says. “I felt like I needed to all the time straighten my hair. It may by no means be in its pure state.”

Coach says her confidence in her pure hair developed in highschool, after she transferred from a predominantly white faculty to a college with extra Black college students. The expertise was liberating: her hair went from being a curiosity to a nonissue.

“Now I really feel very empowered by my hair,” she says. “I believe my hair simply provides slightly razzle-dazzle to who I’m.”

Mayfield, the Florida A&M pupil, calls her expertise a shallowness journey: “I’m reclaiming my very own identification and reclaiming what’s mine.” Generally, she says, it isn’t simple. Nonetheless, “I like myself extra for having the ability to rise up for myself, rise up for my hair, and rise up for what I consider in.”

“Coping with our kind of hair takes hours. It takes a village,” Mayfield says. “However I believe being a Black lady that embraces her Black hair, it makes me succesful to fight something on the earth. If I’m in a position to take care of my curls and kinks, I’m in a position to do every little thing else.”

Get Phrase In Black immediately in your inbox. Subscribe in the present day.