Having grown up in California and now residing in New York, I do know that the unthinkable can occur anyplace. Nonetheless, I by no means imagined I’d get up to a catastrophe in Southern California surmountable to the devastation skilled by Hurricane Katrina.

On Tuesday, January 7, I began my day like some other. It was my final week visiting household in California earlier than heading again house to the East Coast. The winds had been blowing sturdy, and there was discuss of a fireplace within the Palisades. For the time being, I brushed it off. It’s California—small fires occur often.

I spent the day as standard, working errands, researching tales and making ready for the following EBONY cowl launch, when round 7 p.m., the facility went out.

With out Wi-Fi, cellphone service was horrible, so we determined to name it an evening early. Nonetheless, on Wednesday, round 5 a.m., my childhood finest good friend Ashley referred to as, and I instantly knew one thing was unsuitable. She requested if I had checked on my grandmother, affectionately often called “Nana,” as a result of the hearth had unfold into Eaton Canyon, Altadena, and components of Pasadena—the place my Nana lives.

Due to the facility outages, we hadn’t seen a information replace and had no thought how unhealthy issues had been. Panic set in as we instantly referred to as Nana, who reassured us that she had packed necessities—paperwork, garments—and picked up her youthful sister and her husband simply in case they wanted to evacuate.

After that sleep was inconceivable.

I attempted leaving the home to discover a espresso store the place I may work and cost my cellphone. However in all places I seemed, the whole metropolis was plunged into darkness, and it grew to become clear that this wasn’t only a minor inconvenience—it was a disaster engulfing the entire group.

By 10 a.m., our telephones wouldn’t cease ringing. The horror was unimaginable. Family and friends texting updates, every message extra devastating than the final: “My mother’s home is gone.” “My grandma’s home is gone.” Nana’s youngest sister and husband misplaced their house. My dad’s first cousin’s son misplaced his household house. One other household good friend misplaced her home, and this was only a mere fraction of the tragic updates.

Later that morning, we drove to Pasadena to witness the impression of the fires. As quickly as we exited the freeway, ash and smoke crammed the air like a thick, suffocating cloud. Police barricades and blockades prevented us from reaching some streets, however we may clearly see the devastation. Complete houses—gone. Establishments that held a number of childhood recollections had been now unrecognizable. The cemetery the place our family members are buried was consumed, and the church the place we had been anticipating to have a member of the family’s funeral that Saturday was on fireplace. They are saying, “When it rains, it pours,” but it surely wasn’t the rain we would have liked.

Once we lastly made it to Nana’s home, I grabbed the backyard hose and soaked the roof, the yard and the shrubs, praying the water would shield it if the fires crept nearer. After hours of pleading together with her to go away with us, Nana reluctantly agreed. Like many elders who moved from the South a long time in the past, she was tied to her house, and lots of have been unwilling to go away regardless of the hazard.

This wasn’t only a lack of property that one would hope to be recouped by insurance coverage claims. For my household, that is private. Like Nana, a lot of our buddies’ dad and mom and grandparents got here to Southern California throughout the Nice Migration, fleeing the Jim Crow South in the hunt for higher alternatives. These houses weren’t simply the place they lived—they had been symbols of perseverance and sanctuaries of affection, historical past, and tradition, constructed with their very own arms.

Whereas the flames consumed this group, they didn’t simply destroy buildings. They erased a long time of Black generational wealth and heritage. Household images, heirlooms and prized possessions vanished within the smoke. These houses represented fairness, stability and the promise of one thing to go right down to future generations. That promise is now gone.

The loss in Altadena and Pasadena just isn’t an remoted tragedy. It’s half of a bigger, alarming development: the erosion of Black generational wealth. Throughout the nation, Black households are dropping the houses which have served as their monetary and cultural anchors. Gentrification, predatory lending, rising property taxes, and now local weather disasters are wiping out the legacies that had been painstakingly constructed.

What’s significantly devastating in regards to the Los Angeles fires is how sudden and irreversible the loss is. In simply hours, my grandmother, like so many others who spent a long time creating a house that embodied her desires and sacrifices, noticed it taken all away.

As I mirror on this, I can’t assist however take into consideration the larger image. What does it imply for our group when the bodily symbols of our historical past—our houses—disappear? What occurs to Black wealth, delight, and id when the very basis of our legacy is decreased to ash?

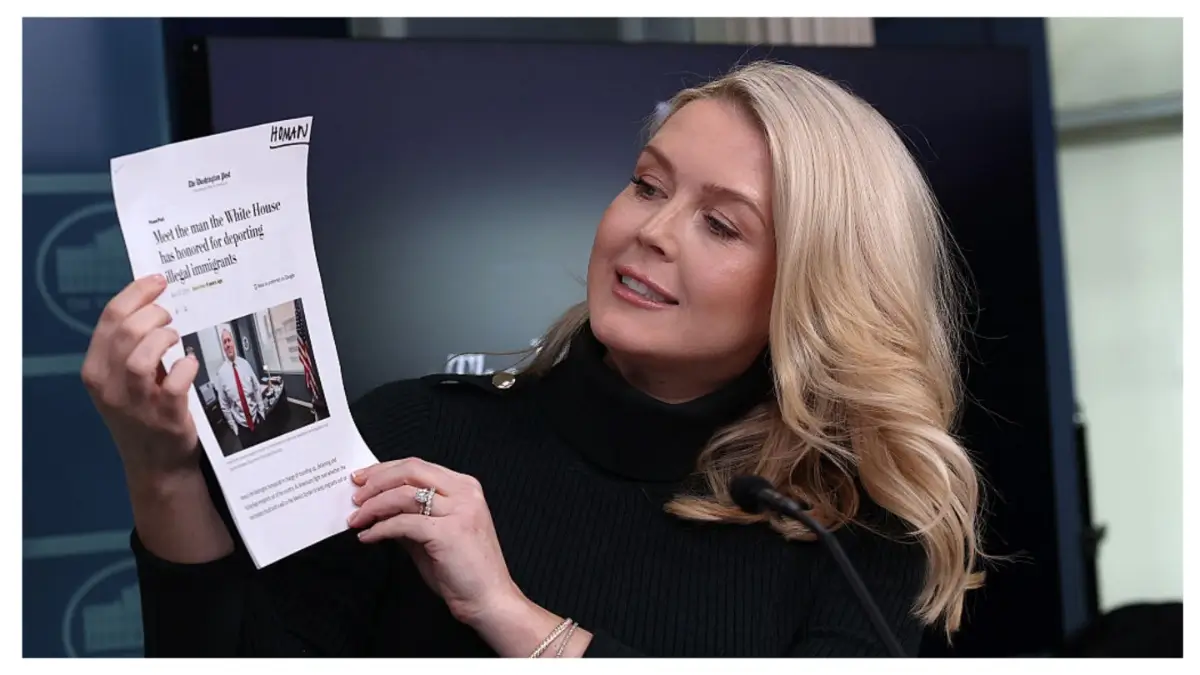

This isn’t only a name to rebuild; it’s a name to guard what stays. We want insurance policies that prioritize catastrophe preparedness in susceptible communities, help for these displaced by local weather change, and initiatives to protect Black generational wealth. Grasping insurance coverage firms dropped fireplace protection from numerous householders’ insurance policies in a single day, solely to reinstate it after intense backlash.

However even with the promise of funds to rebuild, many are saying they won’t hassle—opting to purchase a apartment some place else in California. If that occurs, it raises a chilling query: Is that this precisely what the federal government or these in energy need? To strip Black households of generational wealth, power them out of LA County, and even out of California fully, persevering with a sample of displacement and erasure?

For now, I’m grateful my Nana and family members are secure, however the ache of what’s been misplaced will linger for years. Rebuilding isn’t nearly bricks and mortar—it’s about reclaiming a historical past that’s been burned however not forgotten. The battle to protect Black houses is the battle to guard our future.