Within the shadow of Houston’s gleaming skyscrapers lies Freedmen’s City, a historic neighborhood throughout the metropolis’s Fourth Ward that when stood as a monument to Black self-determination.

The city was born from the labor of previously enslaved individuals who settled there after Emancipation. For generations, the neighborhood has fought to maintain its story alive within the face of contemporary improvement and gentrification through the early a long time of the twentieth century.

As we speak, Fourth Ward is inside miles of Houston’s Midtown and Downtown areas, certain by high-rises and workplace towers. Out of its tons of of historic constructions, fewer than 30 stay.

The neighborhood is at a crossroads. Tax Increment Reinvestment Zone (TIRZ) funds and the Fourth Ward Redevelopment Authority (FWRDA) are pouring {dollars} into rebuilding streets, restoring historic constructions and supporting cultural establishments.

Alongside these enhancements stay laborious questions on gentrification, displacement and whether or not financial positive factors can coexist with cultural preservation.

TIRZs are zones created by the Metropolis Council to draw new funding in an space, serving to fund prices of redevelopment that might “not appeal to adequate market improvement in a well timed method.” The tax {dollars} are put aside in a separate fund to finance these enhancements throughout the boundaries of the zone.

A legacy of self-sufficiency

Miguell Ceasar, division supervisor and archivist on the African American Library, Gregory College, itself a restored landmark in Freedmen’s City, stated the realm is understood to be Houston’s oldest African American group. Counting on one another’s acts of survival and pleasure, forging a secure, self-reliant neighborhood, residents anchored the group spiritually and politically. Colleges like the unique Gregory Institute educated Black kids when segregation barred them elsewhere.

“This was near the Bayou and wasn’t even a part of Houston on the time. The swampy Bayou space was flooding over right here and so they allowed the Blacks to settle,” Ceasar stated.

Ceasar famous the realm, as soon as a flood-prone bayou fringe, turned a self-contained hub with over 400 Black-owned companies, docs, grocers and its first Juneteenth celebrations.

Fashionable efforts to guard historical past

A lot of this previous is preserved due to focused investments by the Fourth Ward Redevelopment Authority, which manages the TIRZ funds devoted to the neighborhood.

Venessa Sampson, the group’s govt director, described the board’s mission as balancing a posh slate of wants: historic preservation, infrastructure upgrades, parks and inexpensive housing.

“We form of do the unsexy (laughs) sort of stuff,” Sampson stated. “You possibly can’t construct a home if the muse is just not proper.”

Main initiatives funded by the Fourth Ward TIRZ, which started in 1999, embrace restoring Bethel Church, rebuilding West Webster and Wiley parks and remodeling the Gregory College right into a public library and archive.

Wrestling with gentrification and displacement

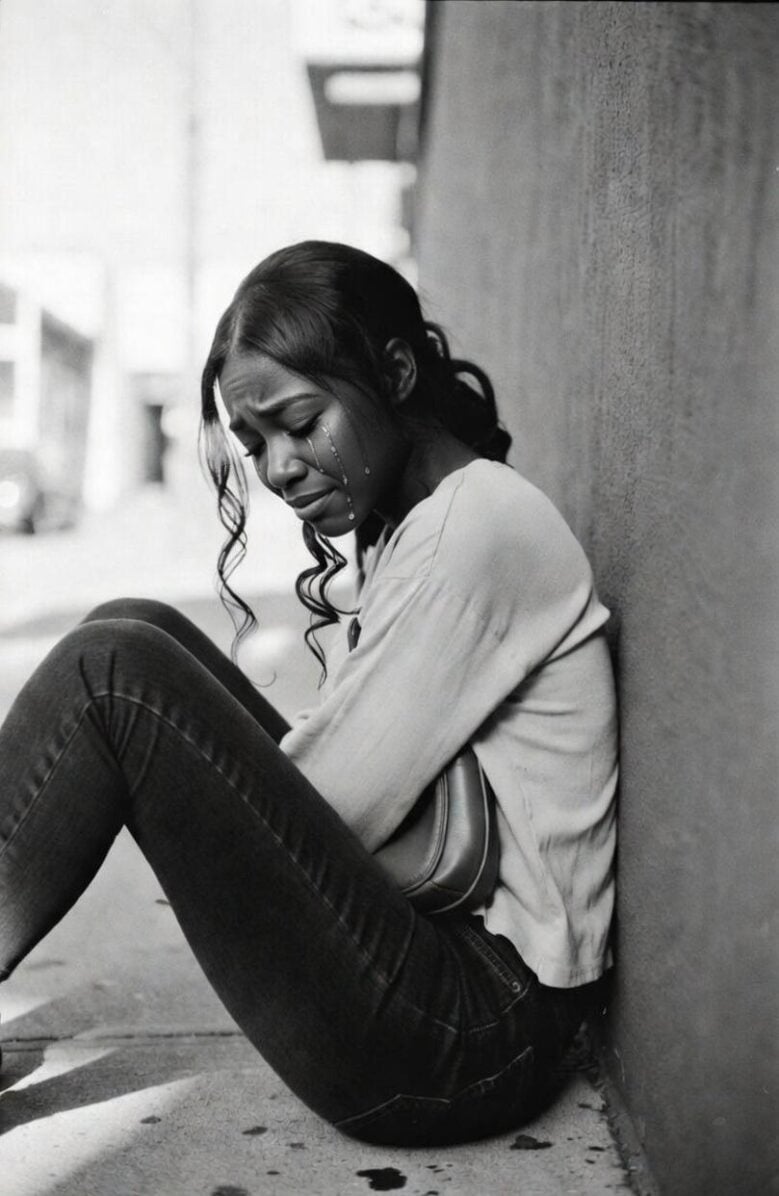

Nevertheless, the progress comes with a painful undercurrent. Being near Downtown, River Oaks, and Buffalo Bayou comes with rising property values, pricing out among the households whose ancestors constructed Freedmen’s City.

“It’s been difficult as a result of we’ve been having to discover a approach to get these seemingly competing pursuits finished in a small footprint, but additionally not having the kind of TIRZ that generates increment in a speedy method,” Sampson stated. “The price of getting initiatives has elevated over time as you’re ready for increments to get you to the purpose the place you’ll be able to truly do initiatives.”

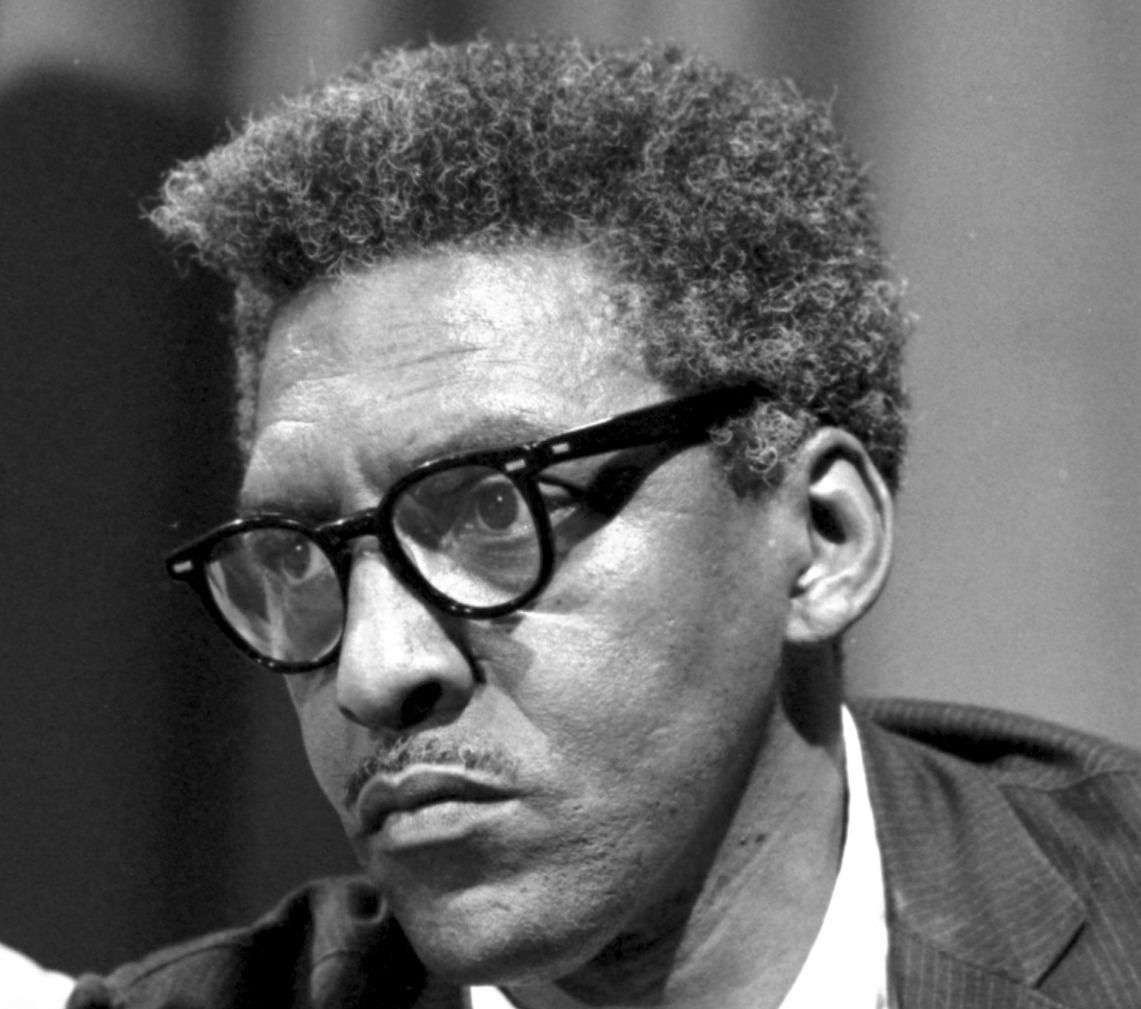

Jacqueline Bostic, chair of the Fourth Ward Redevelopment Authority board and a descendant of Rev. Jack Yates, a previously enslaved man who helped discovered Freedmen’s City and Houston’s Emancipation Park, emphasised this level.

“The Fourth Ward TIRZ has been instrumental in ensuring that the realm continues to obtain tax {dollars}, which work in direction of enhancing the group,” Bostic stated, including the TIRZ ensures Fourth Ward now receives tax {dollars} that when bypassed the neighborhood.

The group has experimented with inexpensive housing, together with pilot houses constructed on properties they acquired from the Metropolis of Houston. However, Sampson warned in opposition to fast fixes earlier than properties revert to market charges and prompt exploring fashions that promote lasting affordability and financial mobility, so residents can construct wealth and keep.

“I don’t know what the reply is,” Sampson admitted. “We’ve got a possibility to mitigate displacement. However how can we do it in a approach that isn’t Part 8 housing, essentially, and isn’t rental property?…It doesn’t matter if you’re Black, brown, white or in any other case, should you can afford it, you simply displace somebody who not can afford to be there.”

Bostic echoed the priority, including that newcomers to the realm will not be chargeable for erasing a neighborhood’s cultural id.

Freedmen’s City won’t ever look precisely because it did a century in the past. However Sampson hopes the work they’re doing will protect sufficient of its soul to information whoever comes subsequent.

“For those who come into the Fourth Ward space appreciating what this group has contributed, then they’re not preventing to have a voice or an id as a result of you’ve got fallen into their house,” Sampson stated. “For those who go to the Second Ward and also you go there with the intent to understand what that group has supplied, they welcome you with open arms. However once you’re making an attempt to take it and homogenize it, they’re gonna struggle for it.”