This text is a part of “On Borrowed Time” a collection by Anissa Durham that examines the individuals, insurance policies, and programs that harm or assist Black sufferers in want of an organ transplant. Learn half one, two, and three.

It’s the Nineteen Sixties. Inside a affected person’s hospital room, cardiac screens beep softly at midnight. The faint rise and fall of a chest. The hum of machines. There aren’t any cell telephones or name buttons. The ground is tough, chilly to the contact — not the sort of place you’d need to sleep.

On many nights, it’s the place Dr. Clive O. Callender, then a younger chief resident at Freedmen’s Hospital in Washington, D.C., lays his head for a nap. Each few hours, he wakes to test on a affected person who has simply acquired a brand new kidney or liver.

It was an unconventional strategy, however Dr. Callender, now 88, says it was essential to hold them alive. He’s, in any case, one of many nation’s first Black transplant surgeons, a place that required him to be higher than good. Within the Nineteen Sixties, he was carrying the burden of proving Black people might be transplant surgeons on his slender shoulders. So Dr. Callender was taking no probabilities.

When he accomplished his surgical coaching in 1973 on the College of Minnesota, Dr. Callender says he grew to become the third Black transplant surgeon on this planet. Over the subsequent six a long time, he devoted his complete profession to saving lives and to making sure Black individuals had equal entry to organ transplants.

With out Dr. Callender, it’s questionable whether or not transplantation for Black people would have gotten to the place it’s right now. He’s, indubitably, a hidden determine on this house. All through his profession, he carried out greater than 600 transplant surgical procedures, skilled a whole lot of medical doctors, and based The Nationwide Minority Organ Tissue Transplant Training Program, or MOTTEP. He’s acquired greater than 200 honors and awards from medical associations for his work. And these days, a number of awards are named after him.

However behind the white coat is a humble, God-fearing man who nonetheless grapples with an inside dilemma: Did his sufferers thrive on the expense of his household?

“I want I may have spent extra time at dwelling with my spouse and my kids, that’s my solely remorse,” he says. “However , I really consider that God got here first, then my sufferers, after which my household.”

The Man Behind the White Coat

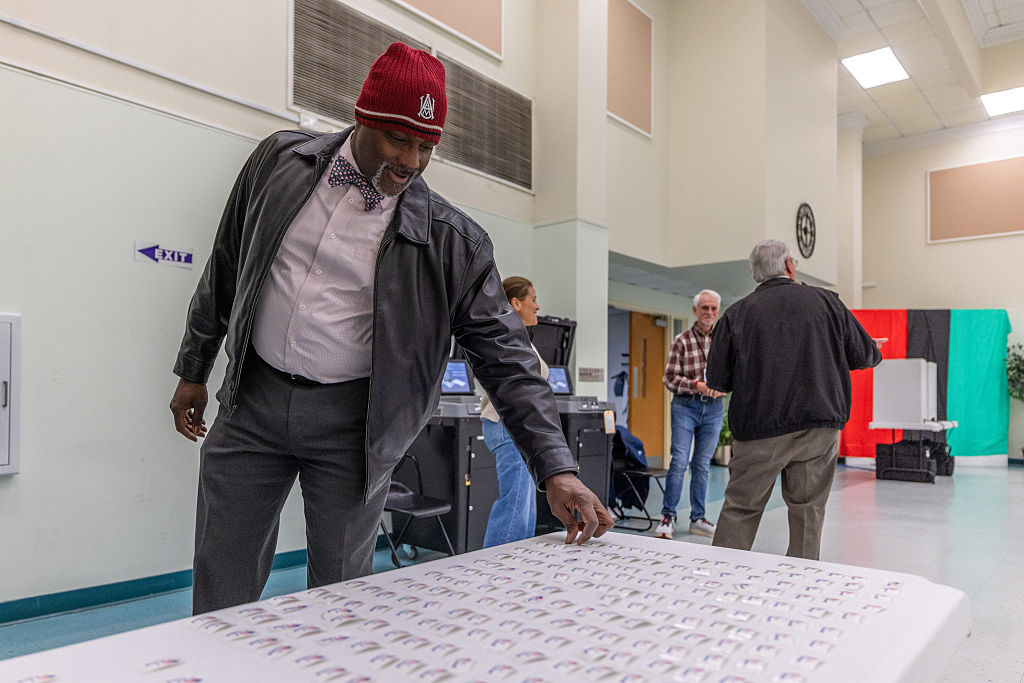

I met Dr. Callender for the primary time on a wet June day in Washington, D.C., on the place he’s spent most of his profession, Howard College Hospital, which was Freedman’s Hospital. He’s a quiet however assured man with a razor-sharp reminiscence. He can identify each individual he’s ever labored with: medical doctors he’s skilled, the pinnacle of the Nationwide Institutes of Well being within the ‘80s, and sufferers he’s transplanted.

Recently, his daughter, Dr. Ealena Callender, drives him to and from the hospital to the brick two-story Maryland dwelling the place they’ve lived for the reason that late Seventies. After our preliminary meet and greet on the hospital, we headed off to the suburbs. It’s a 45-minute, one-way commute. Her Harlem-born and raised father doesn’t drive — he by no means discovered. Ealena tells me that sometimes you’ll see foxes, deer, and squirrels roaming the world.

Inside the home, I left my sneakers on the door, and Ealena confirmed me round downstairs. A light-weight pink plush carpet covers the flooring. White orchids and blush-colored curtains enhance the room. Household pictures and a duplicate of the “New Nationwide Baptist Hymnal” sit atop an upright piano. In the lounge, Callender’s favourite armchair sits in a nook. It’s the place he prays at first and finish of every day.

A big poster of Dr. Callender’s late spouse, Fern Irene Callender, catches my eye within the hallway. She died April 2 — only a few weeks earlier than what would have been their 57th marriage ceremony anniversary. Since her mom’s passing, Ealena tells me she’s taken extra time without work work. However Dr. Callender hasn’t slowed down.

On a Mission to Enhance Black Organ Donors

In 1963, when Dr. Callender graduated first in his class from Meharry Medical Faculty, an HBCU in Nashville, organ transplantation had solely been round for a few decade. He headed dwelling to Harlem for a surgical residency — entering into the transplant house wasn’t on his thoughts. However Harlem Hospital, a instructing hospital affiliated with Columbia College, “handled me like a stepchild,” he says. So in 1969, he accomplished his residency at Freedman’s Hospital.

Not lengthy after, Dr. Callender began sounding the alarm about disparities in organ allocation. It took greater than a decade for individuals to hear. In southeastern states within the Eighties and ‘90s, Black sufferers had the very best price of end-stage renal illness, a situation that finally requires a kidney transplant. But they have been much less more likely to qualify for transplantation, and fewer than 10% of organ donors have been Black.

A part of the issue stemmed from how donor-recipient matches have been made. Antigen profiles are totally different amongst racial teams, however for practically 50 years, physicians recognized and prioritized genetic HLA-B markers discovered primarily in white sufferers. The observe led to increased transplantation charges for white sufferers than Black ones.

In 2003, after persistent advocacy from Dr. Callender, the U.S. kidney allocation system was modified to remove precedence for HLA-B similarity. The outcome: extra transplants for minority sufferers and no drop in success charges.

“It actually didn’t happen to me that I used to be doing something particular,” he says. “Even once you learn papers now concerning the modifications which have occurred as a consequence of my interventions, they don’t point out my identify. It’s due to my talking out, that’s what made the distinction.”

Whereas allocation points have been beginning to enhance, one other query bothered Dr. Callender: why have been Black Individuals much less more likely to register as organ donors?

In 1978, a pilot examine spearheaded by Dr. Callender and funded by Howard College Hospital requested 40 Black women and men in Washington, D.C., about their hesitancy to donate their organs. Dr. Callender and his group discovered 5 fundamental causes: lack of training about what number of Black individuals want organs, non secular beliefs and misperceptions, mistrust of the medical system, concern of a untimely declaration of loss of life if a Black individual is a registered donor, and a choice for Black donor organs to go to Black recipients.

In the beginning of the examine’s interviews, solely two individuals have been registered organ donors. However after a two-hour session, all 40 grew to become donors. Revealed in 1982, the examine set the stage for find out how to educate the Black group and different minority populations about organ donation.

Later that 12 months, the Nationwide Kidney Basis and Howard College Hospital initiated the District of Columbia Organ Donor Mission. By 1989, month-to-month donor registrations jumped from 25 to 750. By 1990, the proportion of Black individuals surveyed via this undertaking who later registered as organ donors rose from 7% to 24%.

In 1991, Dr. Callender conceptualized and based MOTTEP to develop the work of training Black, Brown, and different non-white individuals nationwide about organ donation. He initially requested for a $5 million grant from the Nationwide Institutes of Well being Workplace of Minority Well being however was provided simply $400,000 to arrange websites in Brooklyn, D.C, and Maryland. The next 12 months, he obtained one other $800,000. 4 years later, in 1995, Dr. Callender and his group acquired a $6 million grant to develop to fifteen cities.

“It’s unbelievable. It’s miraculous,” he says. “All we did was educate and empower the group. We allow them to do the job.”

“I’m thrilled and excited to say I’ve been a part of MOTTEP,” he provides. “That is the sort of factor that has made my life price residing.”

‘She Was My Largest Fan’

Fern Irene Marshall was born July 15, 1943, at Freedmen’s Hospital, the identical hospital the place she later labored as an working room nurse. She met Dr. Callender through the fourth 12 months of his residency when she started working with him.

Within the early years of their marriage, balancing profession and household was tough. Ealena says her mother typically advised them Callender was breaking boundaries and saving lives.

“She was my largest fan. No matter deficiencies that I had as a father, she made up for them as a spouse and mom,” he says. “Every part I’ve accomplished efficiently is a consequence of her assist. There’s nothing I’ve accomplished wherein she didn’t assist me. Many of the credit score is expounded to my God and my spouse, and my household.”

His legacy is as a lot hers as it’s his. When requested if he thinks he would’ve made it this far in his profession with out his spouse, his response is instant.

“I don’t know if I’d be alive with out my spouse,” he says.

The President Is Dwelling

Inside hours of his and his twin brother’s arrival on this planet, their mom died from childbirth problems. His older sister, Gloria, named them. Along with his father typically away working, Dr. Callender lived in varied foster houses. He credit his aunt, who helped elevate him, for introducing him to church.

At age 7, he devoted his life to Christ and determined to turn into a medical missionary. His aim was to go to Africa and handle the “souls of mankind.” However issues took a flip for the more severe within the Nineteen Forties when he contracted pulmonary tuberculosis at age 15. On the time, there was no treatment for tuberculosis. After six months within the hospital, medical doctors eliminated half of his proper lung. After one other 12 months within the hospital, he was lastly wholesome sufficient to return to highschool.

That near-death expertise strengthened his religion — and his resolve to honor and glorify God by saving lives. It additionally knowledgeable the kind of physician he was decided to turn into — one rooted in group.

All through her childhood, Ealena remembers her dad’s bedtime tales — mini sagas about rising up along with his twin brother in Harlem, his father working as a chef on segregated trains, and the time he lived along with his stepmother. Each story added just a little extra element and just a little extra shade to the person she calls “daddy.”

When he got here dwelling after lengthy stretches on the hospital, it felt just like the president strolling via the entrance door. Instantly, she and her two siblings would seize onto him and persuade him to take them for a stroll. “We’d simply say, ‘Stroll, stroll, daddy stroll,’” she says.

Even when he was absent, his love as a father was fixed.

“It hurts my emotions when he says he was a awful father and a awful husband,” Ealena says. “Even when he wasn’t bodily right here, he appreciated us and my mom to the utmost. He adored her and revered her. I don’t suppose he took her as a right. He appreciated the individual she allowed him to be.”

Dr. Callender’s dedication to his craft deterred Ealena and her siblings from pursuing medication — at the least, initially. Ealena studied print journalism at Howard and joined the coed newspaper, The Hilltop. After working as a reporter for a number of years, together with a stint on the Los Angeles Instances, she felt a robust pull in the direction of medication, however she hesitated to modify careers. In her eyes, to be a physician meant to observe with the identical depth as her dad — on the hospital for weeks on finish.

“In some unspecified time in the future, my mother mentioned, ‘You don’t need to be your father,”’ Ealena says. “It sounds easy. However it was mindblowing. I didn’t suppose I might be a physician if I wasn’t identical to him.”

Ealena graduated from medical college in 2002. Now a working towards OB-GYN, she says her specialty helps her perceive why her father was so dedicated to his sufferers. They typically despatched pies, truffles, and macaroni and cheese dwelling with him as thanks for saving their lives.

“My father’s legacy is infinite,” she says.

The Street to Transplant Surgical procedure

It’s a miracle that Dr. Callender grew to become a surgeon. After graduating from highschool, he enrolled at Hunter Faculty, one of many campuses within the Metropolis College of New York system. As soon as there, he failed chemistry, English, and historical past courses, and at one level, his GPA was only one.8. Advisors took one take a look at his undergraduate grades and advised him he wasn’t lower out for medication. By his senior 12 months, he raised his GPA to a 2.5, however wanted a 3.5 to get into medical college. On the time, solely two medical faculties admitted Black college students: Meharry and Howard.

His acceptance at Meharry “was to my classmates’ utter shock and mine as properly,” Dr. Callender says. “My twin brother, sister, and father thought I used to be insane for eager to turn into a physician.”

Then the subsequent hurdle got here. Who would pay for it?

As Dr. Callender tells the story, his eyes water and his voice catches. To his shock, Ebenezer Gospel Tabernacle in Harlem held a particular service to lift the funds for his tuition. It’s a day he’s by no means forgotten.

As soon as he grew to become board licensed, he met a Nigerian medical pupil who advised him that missionaries have been wanted in Port Harcourt, Nigeria. So, in 1970, Fern and Dr. Callender signed as much as keep for 5 years. However after 9 months, he returned to Washington, 50 kilos lighter resulting from sickness. He later went again to Africa, alone. Throughout these three months, he contracted malaria and misplaced one other 25 kilos.

It grew to become clear that being a medical missionary was not within the playing cards for him, so he determined to return to the U.S. and dedicate himself totally to transplant surgical procedure. A couple of years later, in 1974, Dr. Callender based the Howard College Hospital Transplant Middle.

“I’ve been via a variety of not possible conditions and I’ve discovered that obstacles are solely stepping stones to success,” he says.

Passing the Baton

Contained in the fourth-floor hallways of Howard College Hospital, photos of Callender line the partitions. A nook convention room bears his identify — it’s adorned with newspaper clippings, analysis papers, and pictures of him performing transplant surgical procedures.

For many years, he’s mentored and skilled a whole lot of scholars, a lot of whom have gone on to turn into transplant surgeons themselves. Edward Cornwell III, now chair of the Division of Surgical procedure, as soon as skilled beneath Callender. They’ve labored alongside one another for greater than 40 years.

“He’s a person with a well-known gaggling giggle,” Cornwell says.

Beau Kelly grew up bouncing between poor Black neighborhoods in Detroit and the Carolinas. He remembers seeing a variety of racism, disparities in well being care, poverty, and drug habit. This surroundings pushed him to review medication, fueled by the need to repair a few of these damaged programs.

Kelly, now a surgical director and liver transplant surgeon at Sierra Donor Providers, says Dr. Callender modified his life whereas he was a med pupil at Howard via a presentation about organ transplantation. Callender grew to become his mentor, and so they textual content virtually daily.

“I’ve by no means had a mentor inform me that they love me,” Kelly says. “He’s the kind of one that spends the vast majority of his time wanting up. He by no means stops making an attempt to realize higher.”

In 2010, Dr. Callender put his surgical devices away. However he nonetheless teaches a category at Howard on transplantation ethics and professionalism. When requested if he’s thought-about retirement, the reply is easy — no.

“I haven’t labored a day in my life,” he says. “It’s been enjoyable. I’ve no must retire.”

With tears in his eyes, he provided due to the sufferers he’s taken care of and his household who’ve stood by his facet. With out them, there could be no Dr. Callender.

“I gave. I gave all I may give.”

Get Phrase In Black immediately in your inbox. Subscribe right now.

Anissa Durham reported this story as one of many 2025 U.S. Well being System Reporting fellows supported by the Affiliation of Well being Care Journalists and the Commonwealth Fund. The Commonwealth Fund additionally helps Phrase In Black’s well being reporting.