The love of self and the love of others are deeply intertwined, in line with everybody from historic philosophers to “Drag Race” host Ru Paul. We have to be anchored in a stable house of self-love with a view to let another person into our lives. On its floor, that is the important thing tenet of Daishi Matsunaga’s “Egoist” (ergo its title). However that sentiment serves as a substitute to spotlight how this maudlin Japanese drama a couple of homosexual man in his 30s dealing with love and loss, not often strikes past the readymade platitudes that litter its well-meaning narrative.

Primarily based on the late Makoto Takayama’s autobiographical novel of the identical identify, “Egoist” follows Saitô Kôsuke (Ryohei Suzuki), {a magazine} editor whose picture-perfect life contains an immaculately designed apartment, a quick-paced job surrounded by style and pictures, a closet full of gorgeous designer garments and a coterie of homosexual male mates with whom he handily will get alongside. And but, from early within the movie, it’s clear there’s a pall over his life. The lack of his mom a few years in the past nonetheless haunts him. The shortage of a love life confounds him.

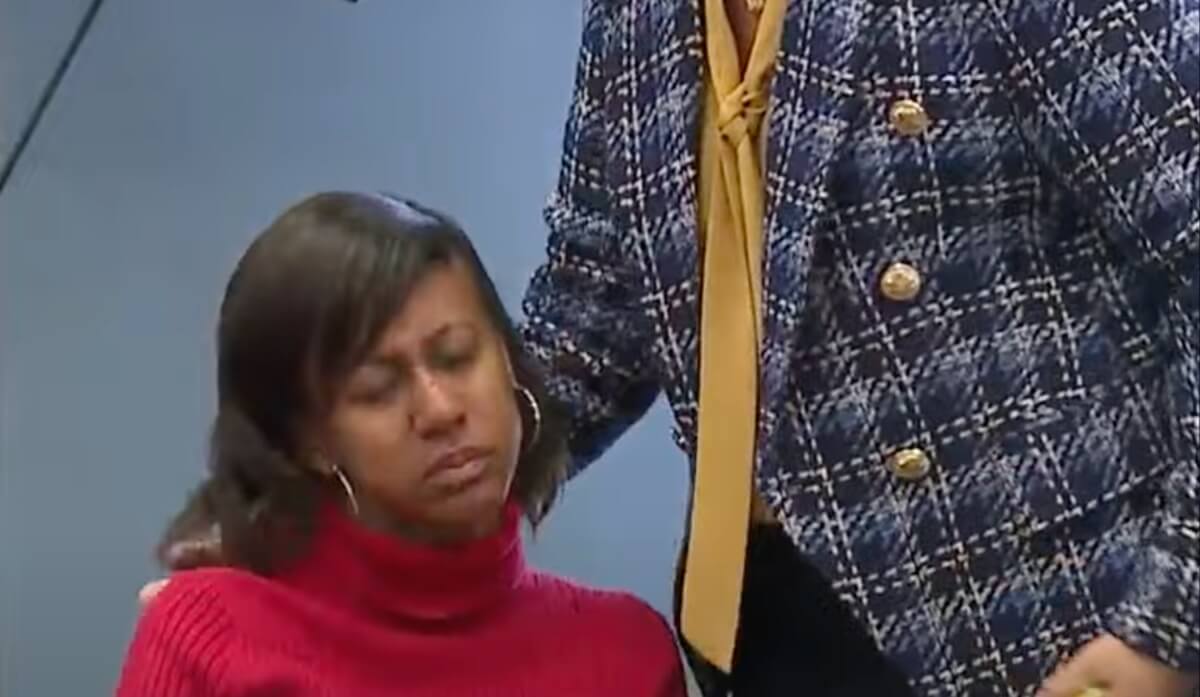

So he hires a younger sizzling private coach, Nakamura Ryûta (Hio Miyazawa). Their chemistry is palpable from their first assembly, and the romance, nevertheless furtive it should stay (the higher to maintain Ryûta’s mom at the hours of darkness about their relationship), is endearing. Quickly, as a cloying montage telegraphs, their budding relationship is in full bloom, with trendy and well-to-do Kôsuke taking the younger Ryûta nearly underneath his wing.

However within the first of many seemingly insurmountable (however quickly sufficient allotted with) obstacles that can come their manner, Ryûta skittishly shares a secret about his life he worries his lover gained’t be capable to overcome. The key is greatest left unspoiled. Nevertheless it forces each halves of the couple to reassess what it’s they need out of life and out of one another.

The load of Ryûta’s confession is shot with a claustrophobically-placed hand-held digicam that fussily detracts from the emotion both actor can be able to conjuring. Matsunaga phases this most pivotal of early scenes with a clumsiness that makes all that follows more durable to purchase into. For strive as Suzuki and Miyazawa do to breathe life into their respective characters, script and cinematography conspire continually to make these two younger males feel and appear two-dimensional, succesful solely of vivid smiles or dour groans, with little in between.

Flirting with melodrama, Matsunaga by no means fairly finds the proper tonal stability between the earnestness of a sun-dappled romance he sketches and the extra miserable story about grief he finally ends up crafting — particularly as soon as Kôsuke will get to satisfy Ryûta’s mom (Yuko Nakamura) and takes a liking to her. Coming after such sentimental plot trappings, the movie’s remaining third-act shock stays largely unearned. That’s as a result of a lot of the dramatic stress that fuels Kôsuke and Ryûta’s love story stays fairly plastic, every revelation and complication so simply ironed out that its narrative and emotional stakes really feel nearly incidental.

And so, whereas the movie hints at some thorny themes round residing overtly in Japan as a homosexual man and the way grief curdles inside you and colours your world, “Egoist” stays a somewhat sedate affair. The movie suffers from a self-serious tone it breaks solely throughout scenes with Kôsuke’s mates, whose transient conversations open up the world of “Egoist” in delightfully welcome methods — solely to then be relegated to minor moments in favor of awkward exchanges between boyfriends, and later nonetheless between the 2 males and Ryûta’s mom. (The intercourse scenes, of which “Egoist” boasts just a few, are so exactingly shot as to really feel somewhat listless, even once they’re presupposed to denote a hungered form of need Matsunaga’s digicam by no means fairly captures.)

With its languid tempo and soap-opera-adjacent plot twists, Matsunaga’s movie finally ends up enjoying like a well-intentioned tragic love story meant to tug at our heartstrings. However the movie ties its many threads collectively so neatly that, like Kôsuke’s residence, its trendy association solely makes it really feel that a lot colder.